The first time I visited Fushimi Inari-taisha was way back in January of 2016. Since then I have been to the heritage site a couple of times but I never came around to writing about it.

The Inari shrine is one of the most popular shrines in Japan. The classical vermillion Torii (gate) with a pair of stone fox images guarding such shrines can be found everywhere in the country. The most striking feature of Inari worship (Inari shinkõ) is the high degree of diversification and even personalization of this kami. Devotees do not simply worship “Inari,” but a separate form of Inari with its own name.

Fushimi Inari-taisha (伏見稲荷大社) is the head shrine of the Kami Inari, located in Fushimi-ku area of Kyoto. The shrine sits at the base of a mountain, also named Inari, which is about 230 meters in height. Most of the shrine’s prominent structures are located right at the base of the mountain. However, for the adventurous types, there are numerous trails that lead right up to the summit of the Inari mountain, where you can find some very old and interesting shrines.

Whichever trail you choose, it is about 3 km to the top. Along the way, you will witness hundreds of smaller shrines, some freshly painted and some, in a somewhat debilitated state. The most intriguing part of the hike, however, are the thousands of vermilion-colored gates called Torii.

Vermilion is said to be a color that repels magical powers and is the reason it is often used in shrines, temples and even palaces in Japan.

Most of you, I assume, would be arriving to Fushimi Inari-taisha from Kyoto via the JR train line unless you are using your personal vehicle. As soon as you get off the train at the Inari Station, you cannot miss the huge Torii gate that leads to the main shrine grounds. The shrine’s close proximity to the bustling city of Kyoto makes it very easy to reach but that also means massive crowds, especially during the weekends. My recommendation would be to reach as early as you can.

The Great Torii of Fushimi Inari Taisha

Visit to a Japanese temple or shrine starts with passing through an exorbitantly designed gate. These ubiquitous gates that form an integral part of every Shinto shrine, vary from shrine to shrine in terms of both size and effect. Made from bronze, stone or wood, they are typically constructed to form a horizontal beam – kasagi, supported by two cylindrical columns called hashira. The first massive gate you pass while visiting Fushimi Shrine is known as the Daiichi Torii. It is meant to indicate to the visitor that he or she is now passing into an even more sacred space.

If you visit the Taisha from Keihan Fushimi Inari Station via Miyuki Road, you will not be passing through this torii gate.

The wooden ones are always colored in bright vermilion. Though commonly built at a scale that comfortably fits a small group of people, they range from miniature torii placed on shrines by worshipers to mighty structures such as this one leading into Fushimi Inari-Taisha.

Beyond the Torii, you will find the entrance gate to the shrine known as the Rōmon gate or Plum Blossom Gate, guarded with statues of foxes on either side. Generally, you will find a couple of lion-dog statues beside the shrine gate, but in the case of an Inari shrine, a fox statue is placed instead of the guardian dog. How the fox began being considered as the guardian spirits of the Inari shrines and messengers of the Gods. I will deal with a little later in this very article.

The Rōmon gate was donated to the shrine by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in 1589

The Rōmon gate along with the entire complex burned to the ground during the Onin War (1467-1477) in the mid-15th century and everything you will see onwards from here is a reconstruction. Beside the Rōmon gate, you can find the Chozuya, to purify yourself before entering the shrine complex.

A brief history of Fushimi Inari Taisha

Fushimi Inari Shrine is dedicated to Inari, the Shinto deity of rice cultivation and business success. This deity is said to grant a wide variety of prayers, from gokoku hojo (better crop output) to shobai hanjo (business prosperity), and in some regions of Japan, anzan (safe childbirth), manbyo heiyu (being completely cured of any illness), and gokaku kigan (prayers for academic success). Owing to the popularity of Inari’s division and re-enshrinement, this shrine is said to have as many as 32,000 sub-shrines (bunsha) throughout Japan.

Inari is a different kami to each believer, shaped by what each person brings of his own character and understanding of the world.

The earliest structures on Mt. Inari were built as early as 711 CE. It was originally erected as their patron deity by the influential Hatas, the descendants of the Korean prince naturalized in the 4th century. The day Inari Okami was enshrined on Mt. Inari is known as “Hatsuuma.” To commemorate Inari’s enshrinement, the Hatsu-uma Festival began to be celebrated every year. It’s been about 1300 years since and the custom is still maintained to this day. The shrine was later re-located to the base of the hill in 816 on the request of the monk Kūkai.

The shrine became the object of imperial patronage during the early Heian period (794-1185). In 965, Emperor Murakami decreed that messengers carry written accounts of important events to the guardian Kami of Japan. These heihaku were initially presented to 16 shrines, including the Inari Shrine.

Inari was first worshipped in the form of three deities (perhaps because there are three peaks on Inari Mountain in Fushimi) and later, from the time of the Kamakura period (1185–1333), as five deities. There has been great variation in the priestly assignment of kami as the three main deities of Inari Mountain; the current tradition of enshrinement, standardized during the Meiji period, is as follows:

- Lower Shrine: Sannomine Uganomitama no õkami

- Middle Shrine: Ninomine Sadahiko no õkami

- Upper Shrine: Ichinomine Õmiyanome no õkami

Another custom that developed during the Heian period was the “souvenir cedar” (shirushi no sugi), a term so popular it became symbolical with the Inari shrine. The custom required one to take a small branch from one of the cedar trees on Inari’s mountain and attach it to themselves as a kind of talisman. It was especially popular to do this on the first horse day in the second month (nigatsu no hatsuuma), the traditional day of Inari’s worship.

In 1875, the name of Inari Shrine was changed to Mizuho Kosha

From 1871 through 1946, Fushimi Inari-taisha was officially designated one of the Kanpei-taisha (官幣大社), meaning that it stood in the first rank of government-supported shrines.

The mythical Fox of Inari

At Inari shrines, foxes (Kitsuné), are regarded as the messengers of Gods. The word Kitsuné comes from two Japanese syllables: Kitsu & ne. Kitsu is the sound of a fox yelping and ne is a word signifying an affectionate feeling. Each fox statue holds a ball-like object representing the spirit of the Gods, a scroll for messages from the Gods, a key for rice storehouses, or a rice ear in its mouth.

One legend suggests that an agricultural cycle is similar to that of a fox’s behaviors and habits, and the routes of the shrine gates are considered to be foxes’ routes. Ancient Japanese people seemed to believe that foxes had mystical powers.

According to the Nihon Ryoki, one of the oldest records, a great number of foxes lived in the national capital of Kyoto in ancient times. According to the Nihon Shoki, the Kitsuné were held in respect as an animal of good omen. In 720 a black fox was presented from the Iga province to Emperor Gemmyo (661-726 CE), the founder of the capital of Nara.

It is said that during the reign of Emperor Kammu ( 737-806 CE), foxes used to bark at night inside the Imperial Palace grounds and sometimes were even seen walking up the stairs of the palace. In the Edo Period (1603–1867), local people established the practice of erecting gates along the path of the foxes on the mountain behind the shrine to protect and fulfill their prayers.

Night Photo-walk at Fushimi Inari-Taisha

The daytime experience at Fushimi Shrine is one of noisy crowds and chattering school children. Because of its close vicinity to Kyoto, the Fushimi shrine is always crowded with the daily wide-eyed tourists from different parts of the world who generally forget to respect the heritage place in their excitement. So this year when I decided to visit the shrine once again, I planned it specifically at night, when it truly becomes magical. The number of tourists also decreases significantly at this time and I can promise you that it will be a much better experience if you choose to do the same.

As you walk out of the JR train station, you will immediately notice a fox illuminated by a beam of light near the station gate, carrying a rice stock in its mouth.

Heritage structures at Fushimi Inari Taisha

The first Torii leads you to another. It is a beautiful sight sans the crowd.

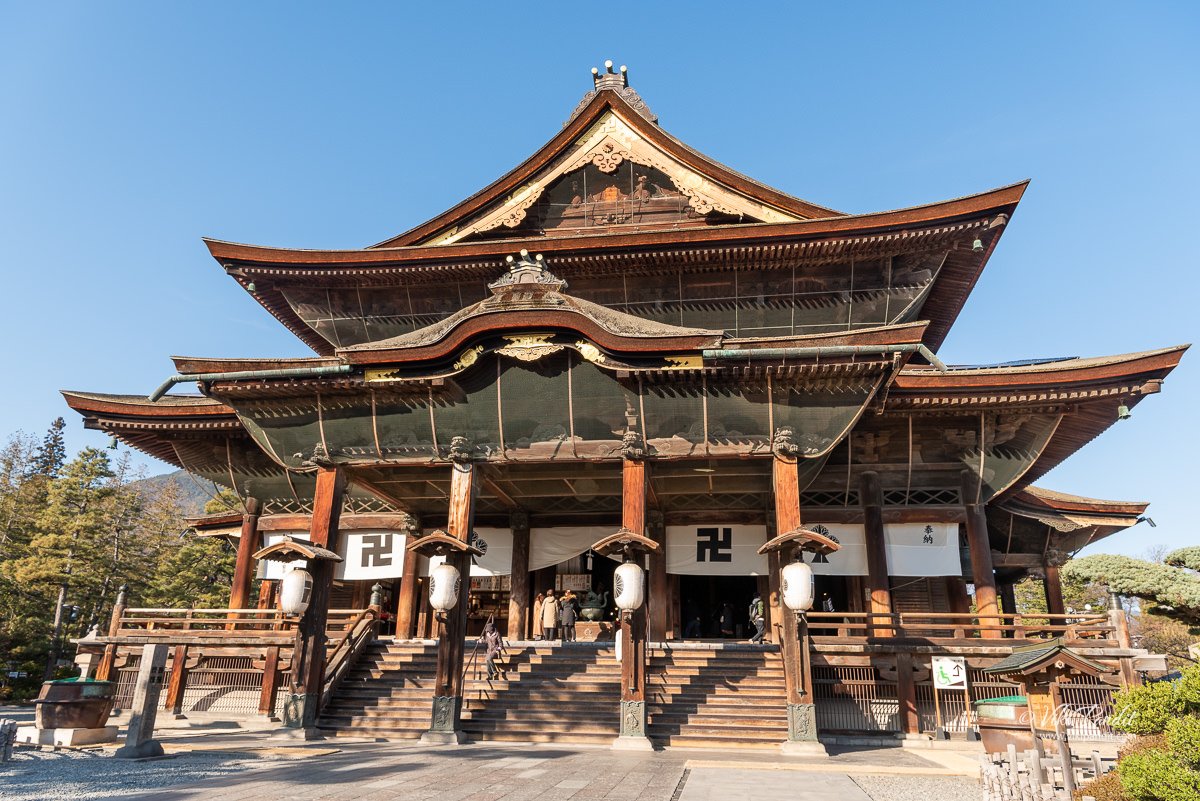

The two-storied Rōmon gate is the building that makes up the main entrance of Fushimi Inari Taisha and has been designated an important cultural property. It was not part of the earliest structures of the Inari shrine, but there is evidence that it already existed around 1500 CE.

The two-storied gate, built with a hip-and-gable roof covered with cypress bark thatching, is believed to have been built during the rule of Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the time from the Warring States period to the Azuchi-Momoyama period. Hideyoshi prayed for his mother Oomandokoro’s recovery from illness, and the gate was built in gratitude for her recuperation.

On both sides of the Rōmon gate are statues of gods called “zuijin” and they act as bodyguards for Inari Okami. Of all the Rōmon gates at shrines located in Kyoto, this is considered to be the oldest and the largest.

Gehaiden

Just beyond the two-storied Rōmon gate, will find the Gehaiden, illuminated brilliantly by the lanterns inside. This brightly lit structure is used for various dance performances during festivals. When I visited the shrine in 2018, I was lucky to experience a dance inside the hall. The hall was then surrounded by hundreds of people and absolutely not like how it is presented below.

The Gehaiden is built with a hip-and-gable roof covered in cypress bark thatch. It is also a designated important cultural property. The iron lanterns hanging from the eaves (edge of a roof) depict the twelve signs of the zodiac.

Azumamaro Shrine

While facing the Gehaiden, on your right you will find a small narrow path that leads to the Higashimaru Shrine enshrining Kada no Azumamaro. On its left wall, you will find hundreds of omikuji and wooden ema plates left behind by visitors.

Azumamaro was active in the mid-Tokugawa period as a priest of the Fushimi Inari Shrine and wrote works including “On Opening Schools and Annotations” to Nihon Shoki. In the modern period, he came to be extolled as one of the four great men of kokugaku or the “Learning of the Imperial Land.”

Prior to Azumamaro, there was Ooyama Tameoki, a disciple of Suika Shinto of Yamazaki Ansai, who also served as the priest of the Fushimi Inari Shrine and studied Shinto as the Learning of the Imperial Land. Kada Azumamaro was from the Hakuro family and Ooyama Tameoki was from the Hata family, these two came from two competing priest families. Yet, they both tried to master the Learning of the Imperial Land through the interpretation of Kojiki and Nihon Shoki.

Naihaiden

Just behind the Gehaiden, lies the main shrine referred to as Naihaiden. It is very close to the Gehaiden at the base of the mountain. A small flight of steps leads you to into the red building. Here you can pay your respects by giving a coin offering, ringing the bells, and praying by bowing twice, clapping twice, praying silently, and then bowing once again. The Naihaiden was also burned down during the Onin War, and the existing building is said to have been rebuilt in 1499.

The main shrine or Honden lies just behind the Naihaiden. It is the holy building where Inari Okami resides. It is also where festivals and prayer rituals are held. The main shrine located within the Naihaiden was built in 1499 in the nagare-zukuri style with its streamlined roof. The 500-year-old building is painted vermilion and is an important cultural property.

Five kami, or gods, are worshipped: Ukanomitamano Okami, Satahikono Okami, Omiyanomeno Okami, Tanakano Okami, and Shino Okami. Collectively, these kami are referred to as Inari Okami. The gables in the entrance are Karaha-fu, a type of cusped gable, and each beam has beautiful Chinese firebirds and flowers carved into it.

Juyosho or Shrine Management Office

This is where you can buy souvenirs like ema plates, amulets, talismans, and the ever-popular omikuji. Applications for prayers, kagura performances, and offerings are also accepted here. The Ema plaques that they sell here are unique. They are called “gankake torii” which are shaped like torii gates. Usually, during the daytime, there is a long queue in front of the counter with a good number of young girls trying their luck at omikuji.

At the inner shrine and at the Gozendani, ema are shaped like white fox faces and called Gankake Myobu Ema. Ema (wooden tablets for writing wishes on) are very popular in shrines and temples around Japan. People write their wishes and leave the tablets hanging up at the shrine where the kami (Shinto deities) can receive them. Usually, ema have a more rectangular shape, but the special ema at Fushimi Inari Taisha is in the shape of a fox. The ema can be purchased at the shrine for ¥500. After purchasing the ema, write your wish on the back, and on the front draw the face of a fox. It is quite similar to Kasuga Taisha, where instead of a fox, you draw the face of a deer. It is very exciting to see all the ema lined up with the different faces that the visitors have left behind.

Gonden

The Gonden is used as a temporary home for the kami when the main shrine or other buildings are being repaired. It is a lot smaller than the size of the main shrine, and it is made in the Gokensha Nagarezukuri style, an asymmetrical gabled roof style with six pillars. It too is a designated important cultural property. The current building is a reconstruction built in 1645. To the left of the Gonden hall, you will find a series of steps that go up the mountain. Climbing this stone staircase marks the beginning of “Inariyama Mikamiseki worship.”

Kami-Massha

This is the Kami-Massha shrine. The big torii to its left goes towards the Okumiya shrine from where the series of torii gates start.

Okumiya Shrine

At the top of the wide stone steps, you will find the Okumiya shrine dedicated to the same Inari Okami as the main shrine. It used to be called the Kamigoten and is made in a different architectural style than the other shrines in the precinct. It also is a designated important cultural property.

To the left of the Okumiya shrine, somewhat hidden by the trees you can find the first of the series of giant torii gates leading through Senbon Torii to the Okusha Shrine.

Continue along the large torii pathway called Myobu Sando and the path will split into two routes with torii gates that stretch tunnel-like. When going to Okunoin from the entrance, pass on the left side. On the other hand, when going down from Okunoin, pass on the right side. That is, we should always keep to the left in the direction we are going.

Senbon Torii

As I mentioned before, the highlight of the Fushimi shrine are the rows of torii gates, known as Senbon Torii. Those who have heard about the Fushimi Inari Shrine, immediately think of the Senbon Torii, or the thousands of red torii gates leading pilgrims up the sacred mountain. The word “Senbon,” literally meaning a thousand is just used here to represent many many more, closer to 10,000. They are so close to each other, that they form an almost perfect tunnel that completely conceals the outside world. Some of the old Japanese literature describes Senbon torii as a tunnel, similar to a birth canal from which a true believer is reborn onto the sacred space on the Kami’s mountain.

Even though I have been here multiple times, I have never thought about counting these torii gates. It is said that there are about 10,000 torii gates lining this road up the mountain to the shrine at the top. This sight of the torii, all lined up is magnificent and, perhaps one of the most iconic views of Japan.

Currently, about 10,000 torii gates stand side by side along the entire approach to the mountain.

After passing through the “Senbon Torii”, you will arrive at Okusha, commonly known as “Oku-no-in”. Legend has it that if make a wish in front of the stone lantern here and lift the empty ring (round-headed stone) of the lantern. It is said that if the weight you feel when you lift it is lighter than expected, your wish will come true, and if it is heavy, it will not come true. From here we turn left and head up into the mountain.

The gateways here are of a brilliant vermillion and black and are engraved with inscriptions from the donors. The custom of donating a torii began in the Edo period (1603-1868.) At times tightly packed and at times irregularly spaced and several yards apart, the torii lead visitors on the 3 km hike up, along the steep hillside, past an assortment of smaller shrines. Strolling up one of the torii tunnels, you will feel lost in a magical red world. It is an almost unreal sensation that washes over you as you venture yet further into the belly of the mountain through this surreal passage.

Some 30 thousand torii are said to have been donated by various people seeking Inari’s blessing on their businesses over the years. Merchants from all over Japan pay large sums of money to get a torii installed dedicated to them, at the shrine. As you move into the next set of torii gates, it does not feel like a tunnel anymore as the gates begin to get separated little by little. The gates here are a little more orangish.

The gates space out more as we head towards the summit. As the torii spread out, the outside light begins to pour into the tunnel and my attention was drawn to the forest that I had entered almost without noticing. The gates here are also not illuminated from the inside so you only have the lights from the street lamps to move around in the dark. The emerging space in alliance with the sequence of columns and beams creates a crisscross of patterns of light and dark.

The path continues upward through the dense cedar forest passing various clusters perched on the hillside until you reach the end of the torii gates.

This area is generally quieter with only the dedicated tourists making it up this far. Being late at night it was almost deserted apart from a couple of young Japanese visitors. A fleet of steep stairs will take you up to a four-point crossroad. The path to your left goes up the hill. On your right, you will find a very narrow lane called the Tamahimesha.

Tamahimesha

This is the Tamahimesha area where you can find many shrines dedicated to Inari. There is a place called Yotsuji in the middle of Mt. Inari. This is a perfect place to rest and you can enjoy the view of Kyoto. The view at sunset is especially beautiful!

Lit candles at a Kanmidokoro Takeya.

This was as far as we went. We didn’t go beyond this point and started our descent back to the base of the hill. During daytime you can hike further to the top of the mountain. While descending we took a different route.

As we reached the base, the Gehaiden was looking absolutely stunning in the night.

It was pretty late at night by the time we started to leave. To my surprise, I could still see some people making their way into the shrine. Yes, the shrine is open 24 hours with both the approach to the shrine and, the Honden itself, illuminated all night. So you can visit anytime you want.

Contrary to general assumption, the Inari Shrine does not own the entire mountain and a number of religious establishments on the mountain are totally independent from the Fushimi Shrine. It is impossible to tell though, which belongs to the shrine. Most guides are also not aware of this division between shrines and private areas.

The pilgrimage tradition at Fushimi’s Inari Mountain that started in the Heian period is still thriving. There’s something to be said about Japan’s almost seamless blend of new and traditional. Never have I seen such a balance of modernism from such an industrious country, all of their technological advances, infrastructure, media, and corporate lives don’t depreciate their respect for tradition and history.

Thanks for reading! Please leave your comments or questions using the comment form below. I am now going to double-check my shopping list before I disembark for India in a couple of days’ time. If you like my stories you can also connect with me on Instagram.

Open 24/7

Free

711 CE

Fox-feeding (Kitsune-segyo)

A custom prevailing in Osaka and vicinity. Believers visit their local Inari shrine carrying a small paper lantern shouting “O-segyo! O-segyo!” a call to the fox that it is feeding time. On their way home, they leave the fox’s favorite food of azuki-meshi, fice boiled with red beans and fried bean curds on the banks or any other place where foxes are expected to go.

Rice Planting Festival in Fushimi Inari Taisha Shrine

Rice has been very important for Japanese people for centuries, and farmers have always worked hard together to cultivate rice. At Fushimi Inari-taisha, you can get a brief glimpse of this ancient Japanese culture. The Shinto rituals for prosperity and good harvests include seeding, planting, and harvest festivals are held respectively on April 12th, June 10th, and October 25th.