After a beautiful evening at the Mullayangiri peak, we were headed back to Bangalore. On the way, we decided to stop over at one of the prominent temples built by the Hoyasalas in Halebidu. Halebidu, previously known as Dwarasamudra, served as the ancient capital of the Hoysalas during the 12th century. The town is home to several scattered monuments recognized by historians as exemplifying Hoysala architecture.

After an hour’s drive, we reached Halebeedu at 7:30 am. We were a bit early and the temple gates hadn’t opened yet. As we parked the car on the roadside, some of the hawkers were already getting ready with their wares before the Sunday crowd could gather. The tea vendor stall was surrounded by people, sharing jokes and sipping on some local concoction of masala tea. A few faithful believers clad in dhoti were engaged in animated conversation also waiting for the temple gates to open. Under the warm embrace of the sun, we savored the simple joy of sipping a refreshing tender coconut water.

As the temple gates opened, we were the first ones inside. From the gate, a long narrow path leads to the remarkable construction that truly deserves its place as “Sacred Ensembles of the Hoysalas” in the UNESCO list of World Heritage sites.

Hoysala dynasty

The Hoysala dynasty reigned over a significant portion of Southern India for nearly two centuries, and left an indelible mark with the construction of remarkable temples, encompassing both Hindu and Jain architectural marvels. No matter what some might say, the Hindus were pretty much welcoming of Buddhism, and apart from some scattered incidents, Buddhist and Jain temples have existed together alongside Hindu temples in several places. One of the most prominent examples is the Cave temples in Badami which hosts a mesmerizing temple devoted to Mahavira and Buddha accompanying several other Hindu gods.

The empire of the Hoysalas extended in Southern India from Mamallapuram and Kanchipuram in the east to the present State of Kerala in the west. Their rule spread to most of the current day Karnataka and also several parts of Northern Tamil Nadu in the Kaveri river belt between the 10th & 14th centuries CE.

The Hoysala dynasty is said to have comprised 14 kings. They were known for their patronage of art and architecture, which forms a crucial part of their legacy. The most popular of the Hoysala kings was Vishnuvardhana, a Jain who converted to Sanatan Dharma and worshipped the Hindu God Vishnu. It was during his rule that the Hoysalas really flourished. After his rule ended, the empire started disintegrating and in 1336 CE. Muhammad Bin Tughlaq (a Muslim ruler from Northern India) attacked the Hoysalas, ending their reign.

Hoysaleshwara Temple

The Hoysaleshwara Temple on the banks of Dorasamudra tank is a masterpiece of architecture and sculpture. The temple is built in a star pattern with 64 corners to accommodate hundreds of deities and other decorative carvings. It was built during the 12th century during the reign of King Vishnuvardhana and is dedicated to Lord Shiva.

As we walked towards the main temple, there were two structures placed tangent to the path. One of them is a weathered carving of a boy fighting a tiger. This is an emblem of the Hoysala dynasty characterized by a majestic and intricately carved sculpture of a mythical lion, often depicted standing on its hind legs. This symbol is prominently featured in many Hoysala temples.

The origin of the name “Hoysala” traces back to the legendary encounter of the dynasty’s founder, Sala, who was the tribal leader of a village known as Angadi (currently within the Chikkamagalur district in Karnataka State) with a tiger. According to popular folklore, Sala valiantly defeated a ferocious tiger, and in commemoration of this brave feat, the dynasty adopted the name “Hoysala,” with “Hoy” meaning “strike” or “kill” in Kannada.

Exactly opposite to the Hoysala emblem, lies a rock-cut statue of Ganesha. It seems to be in a much better state than the emblem. The intricate work on this piece of rock was simply astounding.

As I explore more and more of southern India, it just amazes me as I stand in the presence of these ancient rocks unfolding their silent tales. The Hoysaleshwara temple was earlier also known as ‘Srimad Vishnuvardhana Poysalesvara’ after its patron and was built in 1121 AD. Later epigraphical records recognize it as “Hoysaleswara Panchikeswara” constructed by Ketamalla Dandanayaka, a prominent merchant and other wealthy citizens and merchants of Dorasamudra, in honor of the ruling king Vishnuvardhana and his principal queen Shantaladevi, according to an inscription found in Ghattadahalli, five kilometers east of Halebidu.

According to historical records, it took about 39 years to construct the Hoysaleshwara Temple in Halebidu, yet it remains incomplete in some places.

The temple has four entrances. The one normally used by visitors as main entry nowadays is the northern entrance closest to the parking lot. There is one entry on the south side and two on the east side, facing two large detached open pavilions whose ceiling is supported by lathe-turned pillars.

This view shows two exuberantly decorated dvarapalas, or temple guardians, outside the main doorway approached by a flight of steps. The upper sections are decked with floral and creeper designs. Spread over 7 hectares, the temple complex with deities and pillars are predominantly carved in Steatite (talc-chlorite schist with occasional magnesite and opaque) procured from Turuvekere and Hassan.

The temple was made in star pointed base, further layered with stone carvings systematically. Hoysala temples are not very tall. They are mostly situated on a platform which is 3-5 feet in height. The temple from the base to the crown is approximately 36.6 feet in height. The shikhara or temple towers are absent at Hoysalesvara Temple at Halebidu. There is no clear evidence of its existence in any epigraphical collection.

Dvarapalas at Halebidu are more elaborate than those at most temples. They are about seven feet in height and fierce in appearance like the nio-guardians in Japan. They wear skull-studded crowns endowed with four arms in which they typically hold Shaivite attributes.

Before exploring the outer walls of the temple we went inside the mandap. The temple is a dwikuta- vimana which means a temple with two shrines on the same platform, both dedicated to Shiva. They are two separate shrines with a cruciform platform resting on cruciform-shaped plinths. Both of the temples are preceded by a Nandi pavilion containing ornamented but realistic Nandi bulls. They are respectively called “Hoysaleshwara” And “Shantaleshwara. Hoysaleswara is dedicated to ‘Hoysaleswara’ Shiva (the king) and the other one is dedicated to ‘Shantaleswara’ Shiva (the queen, Shantala). Neither of the shrines have sikharas.

The mandapa (central hall) is held up by pillars. It leads worshippers to the garbhagriha. The spaces between the peripheral columns have been closed off with stone slabs. There are 10 internal pillars around the four much larger ones at the center.

Designed with precision, the temple orchestrates a spectacle known as the ‘Surya Mandala,’ whence the sun’s rays delicately caress the main deity during specific hours. Beyond this celestial alignment, the temple also features many other architectural innovations, such as the use of different types of stones to create various effects, and the use of intricate geometric patterns in its architecture.

In the central navaranga of the shrine, each of the four pillars featured four standing madanakai figures in their pillar brackets for a total of 16 standing figures per temple. These intricately carved damsels, typically depicting a female form, adds visual interest to an otherwise simple pillar. They gaze down upon the devotees below, adding to the beauty of the pillars. Not all the madanakai are in their positions. Of the 32 figures on the central pillars of the two shrines, a total of 11 remain. Only 6 damaged ones have survived in the north temple and 5 in the south temple.

The interiors showcase finely carved, highly polished pillars in myriad profiles, along with exquisite racket figures of dancers and musicians, their sensuality and dynamism expertly rendered in stone. Similarly, ceilings featuring corbelled domes, are adorned with figurative sculptures and with floral, geometric and botanical motifs, the stone resembling wood in its ornateness.

The sanctum walls are plain, avoiding distraction to the devotee and focussing the attention of the visitor at the spiritual symbol. The ceilings of the temple are supported by 12 feet tall pillars chiseled with fascinating grooves, with amazing perfection. Bulbous pillars are found inside the temple, which have carvings that are so precise, that they might have been constructed using some kind of machine.

After paying respects at the temple we came around to examine the intricate carvings on the outer walls depicting scenes from Hindu mythology, such as the stories of Ramayana, Mahabharata, and the Bhagavad Gita. Some of the panels also depict everyday life during the Hoysala period, including dances, music, and games.

The external nandi mandapas (pillared halls built to enshrine the sacred bulls) have been reconstructed in the past, however, they do not affect the authenticity of the architectural form of the temple. Nandi, the sacred bull and vehicle of Lord Shiva, is often depicted in a monolithic form, carved from a single piece of rock. The Nandi monolith at Hoysaleshwara is characterized by its impressive size and detailed craftsmanship. Carved with precision, these sculptures exhibit the strength and majesty associated with the divine bull. The position of Nandi, typically facing the main sanctum of the temple, symbolizes devotion and readiness to carry out Lord Shiva’s will.

The symbolism of the seated Nandi facing towards the sanctum in Shiva temples represents the soul and the message that the soul should always be focused on the Parameshwara (Shiva), the absolute.

From the Nandi shrine, we went on a peripheral walk examining the beautiful carvings on the outer walls of the temple. The Hoysala architectural style has indigenous structural patterns in the form of staggered, star-shaped shrines, positioned on a raised platform with a wide pathway for circumambulation. Hoysaleshwara exemplifies the schema of the tier designs completely on the outer wall of the temple. There are layers of animals and designs, each representing a certain aspect of the Hoysala kingdom. The bottom, the elephants, shows strength, the next layer, lions, shows bravery, the third from the bottom- the symbolic view of flowers- shows beauty, the fourth- cavalry, and then another layer of flowers, to again bring in the idea of artistic beauty.

The layer after that is comprised of soldiers or scenes from Hindu mythology. The third from the top is a layer of makaras (semi-aquatic mythical sea monsters) followed by a layer of peacocks. The topmost layer consists of flowers again to add aesthetics. Above these panels, follows a continuous parade of large-sized depictions of Hindu gods and goddesses, each one incomparable in beauty.

There are more than 240 wall sculptures that run all along the outer wall of the Hoysaleshwara Temple

I have tried to add some of the interesting carvings here. The next capture tells the story of Arjuna shooting the eye of a fish during Draupadi’s swayamvara unfolds in this captivating stone relief.

Skillfully carved, the depiction captures the essence of the archery contest that determined Arjuna as Draupadi’s groom. Arjuna stands poised, his bow drawn with precision, aiming at the revolving fish’s eye. The stone relief immortalizes this pivotal event from the Mahabharata, where Arjuna’s unparalleled archery skills won him the hand of Draupadi, marking a significant turning point in the epic narrative.

This is a figure of a dancing Ganesha with ornately detailed jewelry. The mesmerizing craftsmanship captures the essence of one of the most beloved Hindu deities. Carved with intricate precision, Lord Ganesha is depicted in a seated posture, radiating a sense of divine tranquility and benevolence.

The detailing in the sculpture extends to the symbolic attributes of Ganesha, such as the elephant head, potbelly, and the iconic broken tusk. The sculptor’s skill truly breathes life into the portrayal. The right part of the external wall of the temple starts with an image of a dancing Ganesha, there are almost 240 images of Ganesha in different poses.

Next, we see the Ugranarashima, the fourth avatar of Lord Vishnu. The depiction captures the intense and awe-inspiring moment from Hindu mythology when Lord Narasimha, emerges in his fierce form to vanquish the demon Hiranyakashipu.

The intricately carved details convey the ferocity of Ugra Narasimha, with a lion’s head and a formidable posture. The sculpture skillfully renders the tension and drama of the narrative, showcasing the divine wrath and power encapsulated in stone. The facial expressions, sinuous mane, and the portrayal of the defeated demon beneath the lord’s formidable figure evoke a sense of reverence and awe.

The legend of Jakanacharya

A fascinating legend surrounding the Halebid temples revolves around Jakanacharya, the skilled sculptor credited with their construction. Hailing from Kridapura village in Tumkur, Karnataka, Jakanacharya’s devotion to his craft overshadowed everything, even his familial ties. Entrusted with building the Belur and Halebid temples, he poured his heart and soul into the intricate sculptures.

Unknown to Jakanacharya, his wife gave birth to their son, Dankanacharya, who also later became a renowned sculptor. At Belur, he found a job as a sculptor and noticed a flaw in a figure sculpted by the great Jakanacharya himself. A furious Jakanacharya challenged him, vowing to sever his right arm if proven correct. To everyone’s surprise, Dankanacharya proved his assertion, unaware of his familial connection. In keeping with the challenge, Jakanacharya kept his promise and cut off his right hand even though Dankanacharya insisted not to do so.

Subsequently, Jakanacharya purportedly had a vision where Lord Vishnu instructed him to return to his village, Kridapura, and construct what we now know as the Chennakeshava temple. Following divine guidance, Jakanacharya built the temple, and as the legend goes, Lord Vishnu restored his right hand. Stories of miracles like this should be taken lightly but it is interesting nonetheless. In honor of this skilled sculptor, the Karnataka government annually confers the Jakanacharya Award upon exceptional sculptors and craftsmen.

Back to the continuation of the intricate reliefs. Here we have a relief of Vishnu in the avatar of Trivikrama. Carved with meticulous artistry, it captures the cosmic dance of Lord Vishnu in his Trivikrama form, spanning the heavens, Earth, and the netherworld.

The majestic figure of Trivikrama, with one foot elegantly raised and the other firmly planted, symbolizes the divine conquest of the three realms.

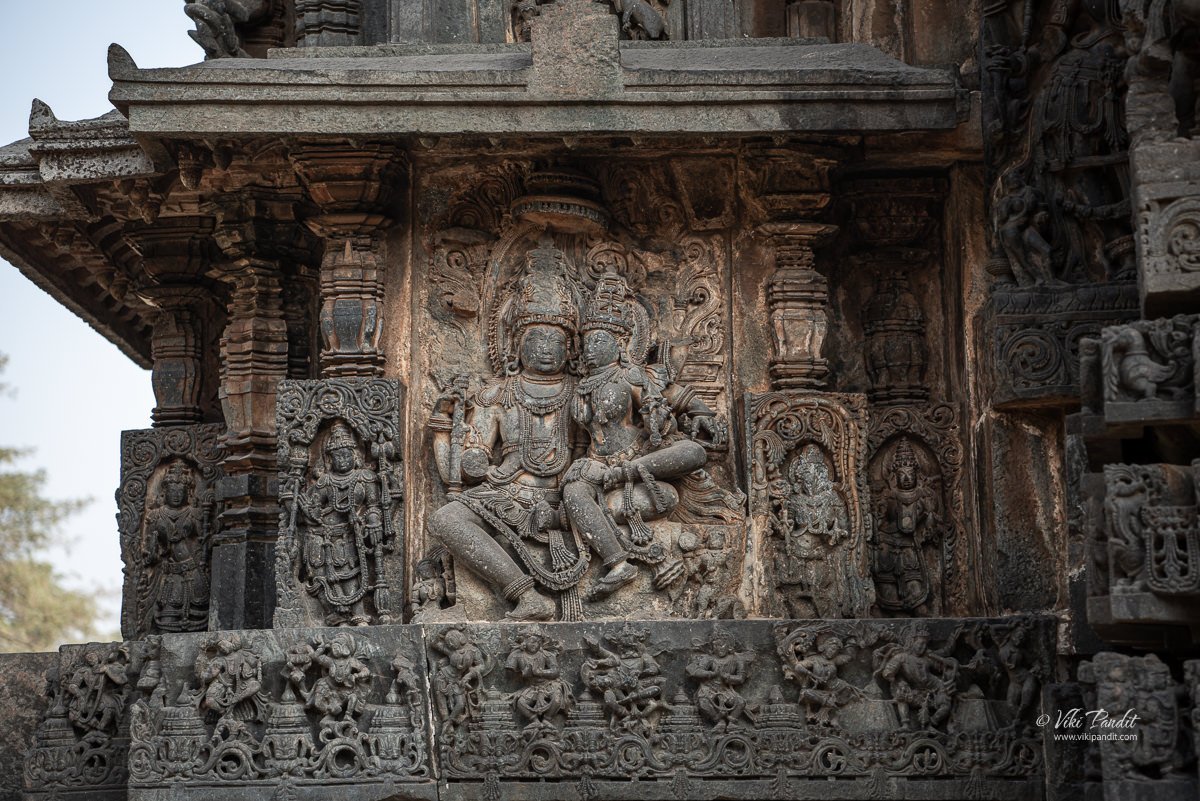

Here we have a panel depicting the Hindu god Vishnu & his consort Lakshmi. The stone carving depicts the goddess Lakshmi gracefully seated on the lap of Lord Vishnu. In this intricate sculpture, both deities are portrayed with exquisite detail, capturing the divine essence of their eternal bond. Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and prosperity, emanates a sense of grace and abundance. She is adorned with symbolic ornaments and holds attributes that signify prosperity and auspiciousness. The intricate details breathe life into the sculpture, capturing the divine grace and serenity that characterizes the celestial couple.

Lord Vishnu, the preserver in the Hindu trinity, cradles Lakshmi in a posture that reflects harmony and cosmic balance. The sculptor skillfully captures the expressions of devotion and tranquility, emphasizing the divine connection between the two deities.

The outer wall paint is creamy brown, and the tallest outer wall reliefs are found in Hoysaleshwara. Among these, one also finds a relief of goddess Kali in the temple which is surprising to most since it is dedicated to Lord Shiva.

Descending to Earth, Krishna astride his divine steed holds the Parijata tree, embodying the essence of cosmic battles. Shri Hari’s countenance reflects his preparedness for the impending conflict, accompanied by the mighty Garuda poised to unleash formidable weaponry. Atop Airavata, Indra and Indrani follow suit, wielding the powerful Vajra. In the culmination, Indra succumbs, and the Parijata finds its eternal abode on Earth.

Horses and cavalry are a prominent feature in the friezes displayed. The cavalry frieze in Hoysala temples showcases depictions of mounted warriors or cavalry, adding a dynamic and lively element to the temple architecture.

Makaras are also extensively used in reliefs. Lions and Makaras are more ornamented than horses and elephants. Reliefs in the temple feature a variety of animals, including bulls, buffalos, monkeys, and peacocks.

Makaras are mythological creatures that are a combination of both land and sea creatures. There are many variations in their form. Makaras designed during the Hoysala period were a combination of crocodiles, pigs, elephants, and peacocks. They were considered sacred and were the vehicle of Lord Varuna. They can be spotted in basement cornices, doorways, ceilings, and various other locations within the temple.

The Hoysaleshwara temple has no less than 1200 carved elephants. They always appear like a disciplined herd, and their positions are related to battle. They are all ridden by warriors or mahouts and are not decked with houdas. There are more than 1400 lions carved in the temple. Almost all of them have raised their tail coiled in identical fashions.

The Hoysaleshwara shows the epics Ramayana and Mahabharata in detail and was one of the first Hoysala structures to do so, similar to the Hazari Rama temple in Hampi. The narrative of the ocean churning is illustrated in a band stretching six feet. Bhima’s confrontation with Bhagadutta extends for about seven feet. The clash between Karna and Arjuna is also depicted, spanning approximately 10 feet.

Ruins of the Hoysala Empire

In the 14th century, the Hoysalas faced defeat at the hands of Alauddin Khilji and Muhammad Tughlak, leading to the plundering of their empire and a significant loss of wealth. This once-thriving city, now bearing the name Halebidu, meaning “old house/old ruins,” never fully recovered and gradually succumbed to neglect. Despite the widespread destruction, a few temples, Halebidu among them, remarkably withstood the ravages of time. When you gaze upon these structures today, the intricate stone carvings will undoubtedly enthrall you, displaying some of the most remarkable expressions in the art of stone craftsmanship.

The temple walls are richly covered with intricately carved sculptures with themes of different forms of the Hindu gods and goddesses, along with stylized animal figures and exquisitely decorative patterns of flora and fauna.

The Hoysala aesthetic emphasized intricacy and hyperreal detail across all levels of sculpture, whether it is pillars, ceilings or wall sculptures. The carvings display a high relief technique, featuring profound undercutting, where artists meticulously indulge in intricacies, capturing every bead, fingernail, or leaf blade with meticulous attention. This lavish ornamentation and unwavering dedication to detail were facilitated by a thorough exploration and utilization of the qualities inherent in Schist, a metamorphic rock. The sculptors deliberately selected this fine-grained, relatively soft mineral for their temples, enabling the manifestation of elaborate and finely detailed sculptures.

Schist is easier to handle, relatively softer and allows for delicate carvings, while granite is harder and one can’t manage the immense beauty achieved in schist. Hoysala-style temples in Halebidu are fine examples of schist sculptures, while the Pallava style in Tamil Nadu is largely defined by the use of granite.

Temples, beyond serving as religious symbols, were the focal point of societal activity. They radiated positive and spiritual energy, becoming hubs for various aspects of life. The temples acted as catalysts for the flourishing of arts, livelihoods, and businesses in their proximity.

Dance and music found encouragement within the temple premises, while vendors and traders established their shops outside, drawing crowds to the vicinity. As a result, temples became convergence points for diverse societal elements, encompassing the political, social, economic, and culture.

Honestly, the visually stunning masterpieces created by Hoysala sculptors on the exterior walls were more interesting than the inside. The extensive sculptures of deities depicting mythological stories foster a much stronger connection with the divine as we walked along the circumambulation path surrounding the temple.

The Hoysalas sculptors are an embodiment of craftsmanship not just from the point of architecture, but also their skills in precision engineering, symmetry, and minor nuances in the sculpturing. Whilst the first look at the architecture awestruck everyone with its intricate carvings; swiftly, it immerses one in the profound thoughts at the engineering abilities of Hoysalas.

The town has many other protected and unprotected temples, archaeological ruins and mounds including multiple Jain temples. There are also some remnants of the fort and gateways that once protected the town.

The Hoysaleshwara temple is considered as one of the most intact and well-preserved examples of Hoysala architecture, and it continues to attract visitors from all over the world. The chisel craftsmanship of artisans from that period infuses vitality into their extraordinary stonework that has captivated visitors for centuries. It is a “must-visit” destination for anyone interested in Indian history, culture, and art.

My heartfelt gratitude to each one of you who took the time to read through my journal. Your engagement and interest mean the world to me. If you liked it, please leave me a comment. If there are areas where you think I can enhance the storytelling, I would greatly appreciate your feedback.

The Hoysaleswara Temple was built during the 12th century, between 1121 and 1160 CE.

Sala, the tribal head from the village called Angadi, located in what is now Chikkamagalur district in Karnataka, is considered to be the founder of the Hoysala dynasty. He laid the foundation for a dynasty that would rule over a significant part of South India for nearly two centuries. Renowned for his legendary courage, Sala is said to have once confronted a tiger barehanded during his childhood and emerged unscathed. You can find a depiction of this event carved in stone at all of the Hoysala temples.

Hoysala dynasty ruled southern Deccan from about 1006 to about 1346 CE.

The capital of the Hoysalas was initially located at Belur but was later moved to Halebidu, also known as Dwarasamudra.

Halebeedu Temple complex is open from 6.30 AM till 9 PM.