Chitradurga Fort is an ancient fortress located in the Chitradurga district of Karnataka. This imposing structure, which covers an area of approximately 1,500 acres, is perched atop a hill surrounded by seven towering walls, making it one of the most impressive fortresses in South India. The city also takes pride in its historical ties to the Mahabharata legend and the mythological figure of Hidimba.

Located at a 3-hour drive from Bangalore, the fort is locally known as “Kallina Kote” or Stone Fortress, formed of two Kannadiga words “Kallina” which means stone and “Kote” which stands for fort. Because of its huge defensive fortification and tenacity to hold up against long aggressive raids, it is also referred to as Ukkina Kote or “Steel Fort”. Situated almost on the highway that connects Bengaluru to Hospet, this is a prominent point of interest in Chitradurga and was the center of Deccani politics for over three centuries.

We were lodged at the Hotel Mayura Durg. It offers excellent value for your money, and the standout feature is its prime location, just a brief 5-minute stroll from the Fort.

Admission tickets to enter the fort can only be purchased using UPI payment apps at the main gate. If you are not using any, you have to visit a website to use online banking to purchase the tickets. At the time I visited the fort, entry tickets for Indian nationals and visitors from SAARC countries were set at Rs. 20 per person, whereas for foreign visitors from other countries, the fee was Rs. 250 per person.

Chitradurga

Chitradurga has a rich history of being ruled by many dynasties. Edicts of Emperor Ashoka from the 3rd century BCE were found near Molakalmuru, a taluk in the same district. To the west of Chitradurga, there was once an ancient city called Chandravalli, where excavations revealed the presence of a prehistoric city.

The fort rests on the seven hills of Chinmuladri range which are some of the oldest granite formations of the Indian subcontinent. As you enter through the Rangayyana gate, the first thing you see is a large water tank known as Kamana Bavi.

The fort’s history dates back to the 10th century when the region was under the control of the Rashtrakutas. Initially, it was mostly a mud fort surrounded by boulders. It was later taken over by the Chalukyas and then the Hoysalas, who added several temples to the fort’s architecture.

In those times between the early 1300s to 1500s, regions like Chitradurga were mostly governed by local chieftains, and the land was largely dominated by Bedar (Valmiki) tribes. The Bedar tribes claim descent from Brahminic rishi Valmiki and trace their origins to southern Andhra Pradesh from where they had emigrated with their herds.

In Kannada language the term ‘Bedar’ means Adivasis or hilly people with mostly hunting as their occupation. The Bedar community is also called as ‘Valmiki’ tribe, ‘Balmiki’ tribe or ‘Beda’ tribe.

However, it was during the reign of the Nayakas in the 17th century that the fort was transformed into its current formidable form.

Timmana Nayaka who was a chieftain under the Vijayanagar empire was given the rank of governor of Chitradurga as a reward for his excellence in military achievements. The first instance of fortification at Chitradurga was by Kamageti Timmanna Nayaka by about 1562 CE. Obanna Nayaka, also known as Madakari Nayaka, declared his independence from the Vijayanagara Empire. In 1602 CE he was succeeded by Kasturirangappa Nayaka, Madakari Nayaka-II (1652 CE), Chikkanna Nayaka (1676 CE), Linganna Nayaka (Madakari III), Bharamappa Nayaka (1689-1721 CE), Hiri Madakari Nayaka, Kasturi Rangappa Nayaka II. The Nayakas of Chitradurga made significant additions to the fort, including the seven concentric walls, which are the hallmark of the fort today.

At its prime, the Chitradurga fort is said to have 19 impressive doors, 38 smaller doors, 4 secret entrances and about 2000 watchtowers.

The fort is structured into seven tiers. Three lower tiers are adjacent to the hill and four tiers are on the slopes of the hill. The first tier has four gates (called Bagilu in Kannada):

- Rangayyana bagilu (Rangaiyya’s gate) on the east

- Santhe bagilu (market gate) on the north

- Seenirina hondada bagilu (sweet water pond gate) on the northwest and

- Lal Kote bagilu (red fort gate) on the south

The entrance of the rocky gateway is adorned with engravings of Gods and a huge snake on the rock wall. These walls were constructed using massive granite blocks, some of which weigh as much as 50 tons, and are separated by moats, which are now mostly dry. Depending on the topography and the geological strata of the land, the fort walls were built with a height ranging from 5–13 meters. Initially, it was built in mud these walls were subsequently strengthened in stretches with granite stone slabs in the 18th century. The three outer walls of defense are provided with deep broad moats.

An outstanding feature noticed in these stretches of the fort walls is that no cementing material was used in joining the large granite cubes that have been neatly sized, cut, trimmed, and placed in position. The total length of the exterior fort walls is about 8 kilometers and covers an area of about 1,500 acres. The narrow winding path leads to Kamana Bagilu, the start of the second tier of the fort.

The Nayak Palegars built the fort as an impregnable fortification for defense purposes with 19 gateways with bent passageways, a palace, 18 temples, 38 posterior entrances, 4 secret entrances, and subsidiary structures like multiple reservoirs, granaries, oil pits, along with 2000 watch towers to guard and keep a strict vigil on the enemy incursions. The storage warehouses, pits, and reservoirs were primarily designed to ensure the food, water and military supplies required to endure a long siege. Underground tunnels were built that served as escape routes in case of an attack. The fort’s strategic importance increased during the Vijayanagara Empire, and it was used as a garrison to protect the empire from invading forces.

Beyond the kamana Bagilu, there is a wide open space. It is up to you to choose which area you would like to explore first. We decided to head straightaway to Maddu Besuva Kallu, an area where gunpowder was ground. This lies in a secluded area on the southern side of the fortress. Once you cross the Kamana Bagilu, turn left and walk about 200m.

Maddu Besuva Kallu which means “gunpowder grinder” contains four stones at four corners similar idea to what we used to have to grind grains to make flour. These were used to grind the gunpowder for the cannons. The stones were powered by the animals either elephants or bullocks, which would rotate them in a circular motion. The grinders have teeth to break the lumps in gunpowder to make it fine so it can be bunt more efficiently with less oxygen inside the cannon chamber. A gunpowder storage room is also located near this place.

From Maddu Beesuva Kallu, we walked to the Chitradurga Fort jail. These are located directly opposite to each other but we wanted to cover these areas before hiking up the hill toward the upper echelons of the fort

The fort is situated on massive rock foundations and the view from the fort features towering boulders. The structure has been built with seven concentric fortification walls each of which has narrow passageways and gates. Thus, it is also known as Yelu Suttine, meaning “fort of seven circles”.

Chitradurga Fort Jail

One of the notable features of the jail area is the presence of a massive cannon. This colossal cannon, with a length of 22 feet and a weight exceeding 50 tons, served as a formidable defender of the fort in times of conflict. Its immense size necessitated the efforts of more than 100 men for loading and firing, and it boasted an impressive firing range of over 2 kilometers. This location within the fort receives relatively fewer visitors.

This cannon, one of two 18-pounders abandoned at the Tipu Sultan Battery on the northeastern corner of the fort, was cast in 1792 at the Carron Works in Falkirk, Scotland.

From the jail area, we backtracked towards the Kamana Bagilu gate to explore the upper reaches of the fort.

This stupendous fort has witnessed some of South India’s bloodiest wars. The fort successfully repelled a near-constant stream of would-be invaders until 1779, when it fell to Hyder Ali of the Kingdom of Mysore. It was during the reign of Madakari Nayaka, the city of Chitradurga was besieged by the troops of Hyder Ali. A chance sighting of a woman entering the Chitradurga fort through a crack hole in the rocks led to a clever plan by Hyder Ali to send his soldiers through the crack hole.

Chitradurga was under siege for almost two years before Hyder Ali was able to capture if from Madakari Nayaka.

Twenty years later, the British forces defeated and killed Tipu Sultan in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War of 1799 CE. Between 1799 and 1809 CE, Chitaldoorg, as the British pronounced it, was garrisoned by British troops as it was perceived to be a potentially useful base along Mysore’s northern line of defense. Later, the fort was handed back to the Mysore government.

Britishers who captured the fort from Tipu were not able to pronounce Chitradurga and called it Chittaldroog

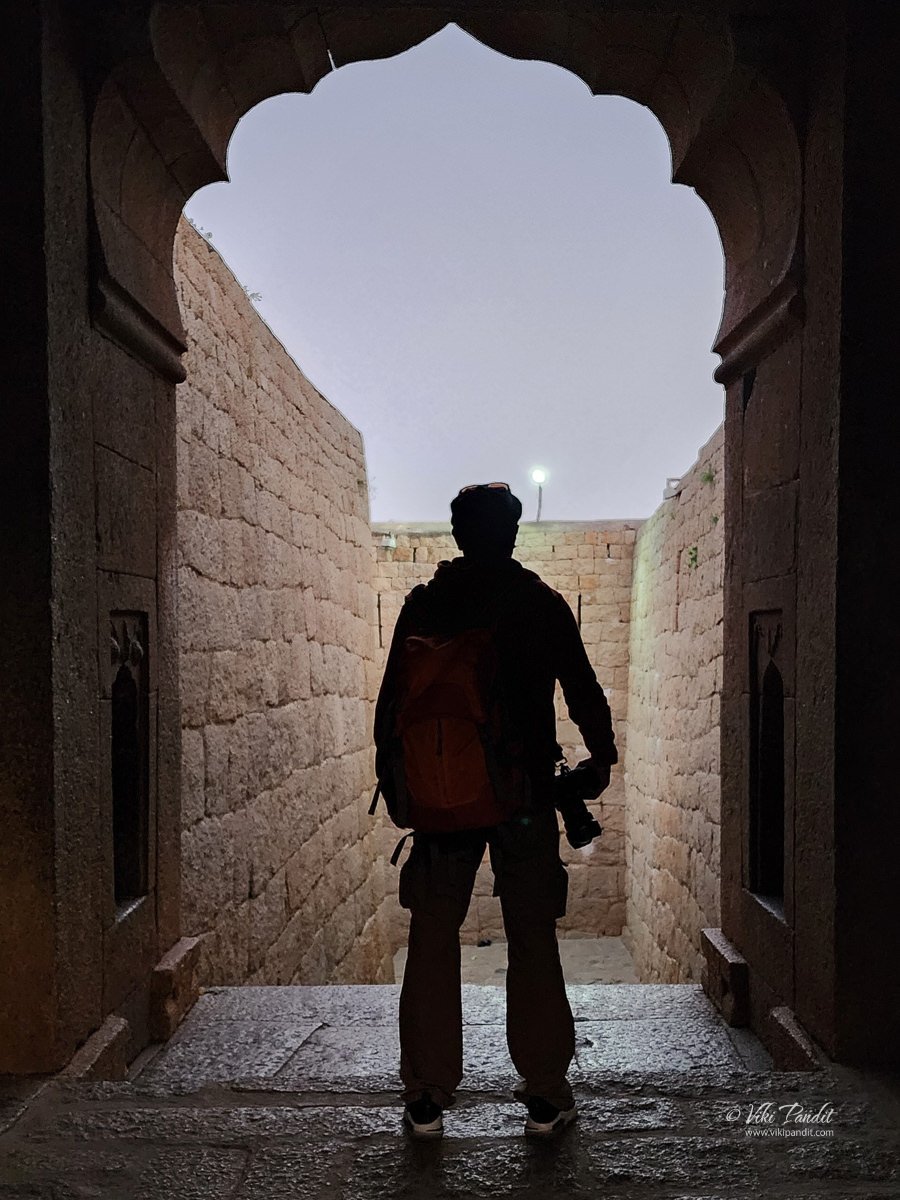

Many of the fortification lines possess elaborate gateways. Among the elaborate gateways, this gateway to the east of the fort has architectural features typical of the Bahmani Sultanate in Northern Karnataka.

The stairs keep going up toward the upper part of the fort where we can find a number of temples in a cluster. There are 14 important temples in the fort. Among them, Hidimbeshwara, Ekanatheshwari, Sampige Siddeshwara, Gopalaswamy, and Phalguneshwara are the important ones.

The presiding family deity of the Nayakas of Chitradurga was Goddess Ekanatheswari, an incarnation of Adi Parashakti. Ekanatheswari’s footprints are sculpted into a block of stones at the entrance of the fort. Some of the well-known temples were the Hidimbeswara, Sampige Siddeshwara, Ekanathamma, Phalguneshwara, Gopala Krishna, Lord Hanuman, Subbaraya and Nandi. Some of the temples have shikharas in Chalukyan style. The Siddheshwara and the Hidimbeshwara have shikhara that resemble a festive chariot.

Shri Ekanatheshwari Devi Temple

The gateway leads to its south leads to Hidimbeswara temple, one of the oldest temples on the hill. This temple is dedicated to the goddess Ekana, Ekavati or Ekanatheshwari. In ancient times, devotees used to sacrifice male buffalo here.

From the Ekanatheshwari Devi Temple, there are two paths, one leads east towards a walled compound popularly called the Mint, and the other leads south, towards the Hidimseshwara Temple.

Tankasale – Mint

These remnants of stone-mud walled structures are believed to have functioned as the administrative hub of Chitradurga Fort during the Palegar rule. Within this administrative center were the Darbar Hall and the Treasury/Mint. These mud walls have endured for approximately half a millennium.

Embedded within these walls are wooden columns, likely supporting the building’s roof with wooden beams. Surprisingly, even the wood from that era has remarkably well-preserved itself. The soil used in these walls is meticulously chosen, likely sourced from a lake bed. The mud is meticulously dried, then finely ground and sifted to obtain a uniform powder. Afterward, it is blended with water and thoroughly mixed until the entire mixture achieves uniform consistency. This procedure demands significant labor and is meticulously overseen at every stage to ensure quality and security, guarding against potential sabotage.

A narrow path beside the Mint leads to a wide open area where we can find a bridge over the Akka and Tangi ponds. There are several other points of interest on this path. A road leads past the Mint to the main western gate, called Basavana Bagilu, and another line of fortifications, which protect the inner fort.

Akka and Tangi Honda

Akka Thangi Honda stands for two massive ponds named Akka Honda (elder sister pond) and Thangi Honda (younger sister pond). These are part of the Fort’s well-planned and sophisticated rainwater harvesting and water conservation system.

The excess water collected in Gopalaswamy Honda flows into Akka Honda and then gradually to Thangi Honda. The pond where 2 queens of Nayaka king drowned after Hyder Ali succeeded in his 3rd attempt to capture the fort. This was a ”jauhar” of its kind.

From here a long winding path toward Gopalaswamy Temple.

We stopped for a breather at this gate just before reaching Gopalaswamy Temple. Garuda and Aanjaneya are carved on either side of the entrance.

A few feet ahead, a freshwater channel flows all the way through the passage that leads to the entrance. A freshwater pond is seen to the left side as soon as we enter. The pond named after the temple – Goplaswamy Honda (pond) is a tank that gathers rainwater from the hilltop. The greenery surrounding the pond is like a mini-jungle amidst a rocky terrain. The Gopalswamy Honda in front of the temple was one of the main water sources for people residing inside the fort.

The vast open space between the palace complex and the Honda is known as Sringara tota referring to the beauty of the landscape. The honda was a part of the palace complex and probably meant for the exclusive use of the royal family. The corner is where palace attendants would draw up water since that’s the closest to the palace complex.

The Gopalaswamy Honda is the largest waterbody inside the fort. This manmade waterbody serves as a mini reservoir nestled in a valley. A 45-meter-long stone wall across the valley is the dam that blocks the flow of rainwater in the valley creating a reservoir that is 50m at its widest point and 140m at its longest point. As to the depth I was told it could be around 10 to 12 feet in the middle.

Gopalswamy Temple

One of the most impressive features of the fort is the steep climb to the top. There are over 2000 steps leading up to the peak of the fort, which can take anywhere from 2 to 4 hours to climb, depending on your fitness level.

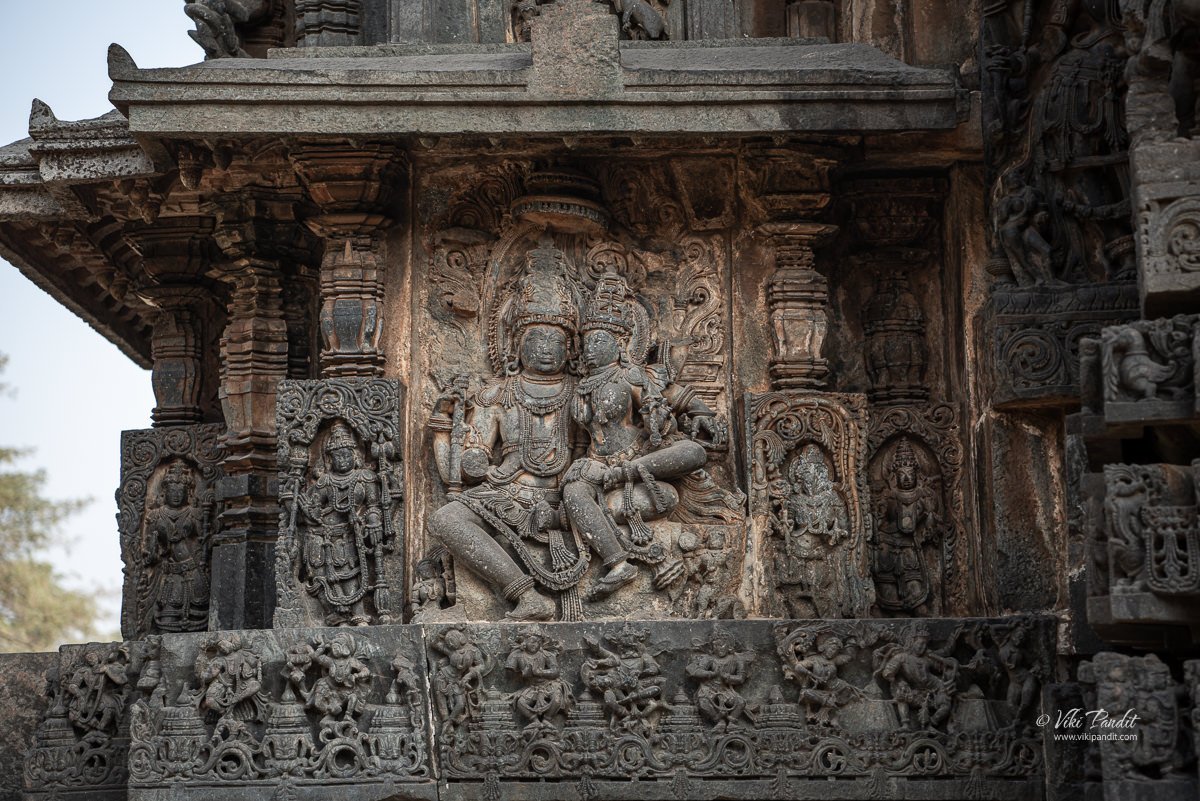

This temple facing east is of Dravidian order with the usual garbhagriha, sukanasi, a six-pillared navaranga. a large four-pillard closed mukha mandapa with a closed passage around the garbhagriha for circumambulation. In the garbhagriha is an image of Gopalakrishna measuring 1.05 m in height from sometime in the early 14th century CE.

There is a reference to this temple in an inscription from 1338 CE. The figure of Gopalaswamy stands cross-legged, playing a flute. On either side of the image, you can see cattle listening to the flute. The sukanasi doorway is flanked by dwarpalas. In the navaranga images of Ganesha, Garuda, Brahma, and Vishvaksena adorn the walls. The ceiling has a large shallow dome fashioned into a lotus. The beam features more images of Indira, Krishna, and other deities.

The climb is challenging but rewarding, as it offers stunning views of the surrounding landscape and the fort’s architecture. While coming down from the Gopalswamy temple, we took a short detour to the Obavve onake.

Obavve onake

When the fort of Chitradurga was attacked by Hyder Ali, according to a legend there was a woman by the name of Obavva, the wife of a guard at the fort, who is said to have single-handily killed several of Hyder Ali’s men who were entering the fort through a small hole in between the rocks. She fought them off with a pestle (onake) and thus this legend is famously called the Obavve onake legend.

During that time, Hyder Ali attempted to capture the fort during the reign of Madakari Nayaka V, the last Nayaka ruler. The structure had a crevice that was discovered by Hyder Ali’s army. However, when Ali’s men attempted to squeeze through this crevice at night, a woman was guarding it on behalf of her husband.

When the brave woman noticed this, she killed the trespassers by hitting them with a pestle. When her husband returned, he discovered the bodies of dead soldiers in the fort’s crevice. He informed Madakari Nayaka and his soldiers about the invasion right away. Hyder Ali, however, was successful in invading and conquering the fort and the last Madakari Nayaka and his family was imprisoned at Srirangapatna.

Nonetheless, the brave woman’s story was not forgotten. History of the fort still remembers her courage and love for her land. Obavva’s courage has been memorialized in Chitradurga by setting up the Onake Obavva Stadium and a life-sized sculpture near the District Commissioner’s Office in Chitradurga.

From Obavve onake, we walked back to the Ekanatheshwari Devi Temple from where we hiked further south up to the Hidimbeshwara Temple.

Hidimbeswara temple

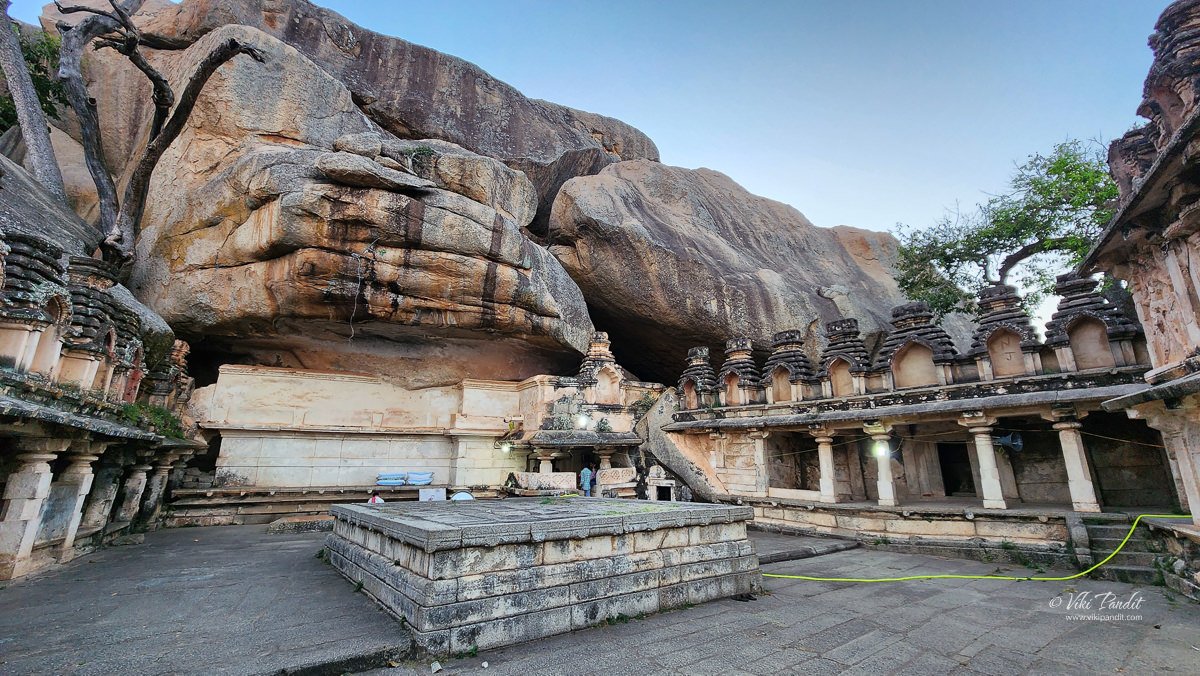

Hidimbeshwara Temple is dedicated to Lord Shiva and is believed to have been built during the 15th century. It is the oldest temple in the area, situated above a massive boulder crowned with a stone superstructure. Within this temple is a sanctum (garbhagriha) housing a linga. On the front side of the outer sabha mandapa, there is a small mukh mandapa (porch) with bench-like seating. The temple’s pillars exhibit diverse designs, featuring octagonal or hexagonal shafts with ornamental details near the top.

The sole captivating feature at this site is the standard representation of Virabhadra, positioned in the navaranga and affixed to a base adorned with a bas-relief displaying seven horses on the front, symbolizing the Sun god, Surya. At the top of this structure is the smallest chamber, crowned with a square stupi. An ancient stone inscription from 1286 CE, found in the outer navaranga, records the generous grants made by Perumale Bandanayaka to the temple.

Myths surrounding Hidimba

The Hidimbeswara temple houses the tooth of Hidimba, the formidable giant (Rakshasa in Sanskrit). The legend goes that Hidimba and his sister Hidimbi once resided on this hill. Hidimba was a source of great trouble for the local populace, and when the Pandavas arrived in the area, they too encountered his menacing presence.

According to the ancient tale, the hills surrounding the fort held great significance during the time of the Mahabharata. Hidimba, the fierce giant, was believed to have inhabited the Chitradurga hill and caused fear among the inhabitants. When Bhima was in exile, traveling with his Pandava brothers and mother Kunti thousands of years ago, he crossed paths with this demon.

There you can find a piece of bone much larger than that kept in the Hidimbeshvara temple, believed to be the tooth of Hidambasura.

Bhima was challenged to a duel by Hidimba, and in the ensuing battle, he defeated and vanquished Hidimba. The boulders in this area are also believed to have been utilized as weapons during their epic confrontation. Hidimbi, who fell in love with Bhima (the second of the Pandava brothers from the Mahabharata legend), went on to marry him, and together they had a child named Ghatotkacha.

Mahadwara

In front of the Hidimbeshwara temple, on a lower level is a three-storied stone tower (Mahadwara) with pillared verandas on the sides. It appears to have been built in 1411 CE by Mallana Odeyar, a relative of Devaraya of Vijayanagara.

Sampige Siddeshwara Temple

A monolithic pillar and two swing frames lie between the entrance to this gateway and the Sampige Siddheshvara temple, which rests at the foot of the hill in the left background. This temple was built by Thimanna Nayak in 1568.

The Gaalimandapa which is the Mahadwara of the Siddheshwara temple is more elaborately designed with a series of pillars in the facade of the second storey on all sides. The mandapa was constructed in 1355 CE while the torana was made in 1411 CE by Mallana Odeyar.

The prominent among them is the Sampige Siddeshwara Temple. The temple of Siddeshwara is a cave temple associated with a hillock named Mukthi Shivalaya Shikhara (abode of Shiva-pinnacle). Located on the southern side, the temple gets its name Sampige Siddeshwara because of the Michelia Champaca, the magnolia flowers, called Sampige in the Kannada language.

This Temple is named after the Sampige tree, which was planted by the Madakari nayaka’s ancestors. It is said to be named after the Sampige tree which was supposedly planted by the ancestors of Chitradurga ruler Madakari Nayaka. This temple is situated at the base of a massive rock formation. Atop the rock formation is the Kavalu Battery

The temple comprises a mukha mandapa, sambhamandapa, sukanasi, and a garbha griha, all axially located. We took a short stroll through the temple to explore the sanctum, vestibule, and hall. Inside the sanctum, you’ll find a daily worshiped Shiva Linga known as Sidhanta, which gives the temple its name, Siddheshwar. The veneration of this deity is linked to Veerashaiva Saints such as Revannasiddha (Sri Revana Siddeshwara Swamy is considered one of the eminent Saints of the Shaiva Sect within Sanatan Dharma).

In the sukanasi you can find images of Nandi and Parvati. It leads to an enshrined linga, better known as Siddheswara Linga. On the south wall is a niche containing a relief group in which two chieftains are depicted with daggers a their girdle in ceremonial attire, holding a linga each in one hand and a pike in the other.

The hall has sculptures of Allama Prabhu, Ganesha, Shula, Brahma, Nandi, Bhairava and several Naga stones. At one corner there is an impressive statue of Veerabhadra.

In the courtyard, there is a huge squarish platform where the palegars and chiefs of Chitradurga Fort were crowned once. In its heyday this place must have seen a lot of ceremonial activities, now it is bare and mute.

Murugharajendra Matha

Murugha Matha was built during the reign of Bharamanna Nayaka (1689 – 1721 CE). Bharamanna Nayak made many additions to the fort and built the Murugha Rajendra Matha, which since then has been the residence of a well-known guru of the Lingayats. The Matha is a spacious and impressive two-storied stone structure, with a pillared hall and a gateway known as Ane bagilu (elephant gate)

Archeological findings at the Chitradurga

Through excavations and investigations in the vicinity of the town of Chandravalli, a recurring sequence of two distinct cultures has been unveiled. This sequence begins with the Neolithic culture, followed by the Iron Age Megalithic culture, and subsequently transitions into the Early Historic period, notably the reign of the Satavahanas.

Several Satavahana coins were unearthed at the outset of the last century. Evidence of the Neolithic culture, such as pottery, has also been discovered in the area. The presence of cupules and engravings of human and horse footprints is discernible within the fort, and intriguingly, cupules have been identified on the dressed stone blocks comprising the fortification wall.

Rainwater-harvesting structures were built in a cascade development, which ensured large storage of water in interconnected reservoirs. It is said that the fort precincts never faced any water shortage.

Historical linkage has been established by an archeological inscription dated 1284 CE found in the Panchalinga (Five Lingas) cave in the Ankhi Matha area, to the west of Chitradurga. The inscription attributes the establishment of the Five Lingas (aniconic symbols of Lord Shiva) to the Pandavas. At Ankhi Matha, approached by stone steps, a series of ancient subterranean chambers cut out at different levels are seen, in addition to several places of worship and platforms

Carvings of the edicts of Ashoka dating to the 3rd century BCE have been found at the fort, and a legendary duel described in the Mahabharata between the hero Bhima and the demon Hidimbasura is said to have taken place on its grounds.

Chitradurga Fort is a magnificent piece of ancient architecture and human skill. Its imposing walls and intricate architecture serve as an important reminder of the rich history of Karnataka, and its conservation and preservation are crucial to ensure that it remains a part of our heritage.

Despite its age and the wear and tear of time, the fort remains an impressive sight, and its architecture has stood the test of time. Visiting the Chitradurga Fort was an unforgettable experience. The fort’s imposing walls, steep climb, and stunning views make it a must-visit destination for anyone interested in history, architecture, or nature. The magnificent fort is now maintained by the Archaeological Survey of India. Though signs of deterioration are visible in the fort today, its sheer size, complexity, and detailed design, and the valor of those who gave their lives to protect it, speak volumes of its glorious past.

Faqs

Summers can be extremely hot and not advisable for the huge area that requires you to climb several stairs.

June – September

English, Hindi & Kannada

The fort is not disabled-friendly

Tripods are not allowed inside the fort premises. If you are carrying a tripod, you will have to keep it at the front office at your own risk.

Tickets must be bought at the front gates, and entrance fees are ₹20 for Indian citizens and ₹250 for foreign nationals.